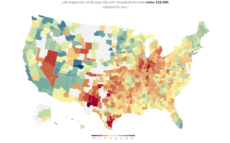

In a well-researched study by Chetty et al. published Monday in The Journal of the American Medical Association and discussed in this excellent article by the New York Times, a new pattern emerges that reveals the discrepancy in life expectancy between poor and rich. What the researchers discovered is that geography is a larger factor than wealth.

As the NYT article states:

The research, in the works for nearly three years and based on a vast trove of records on earnings and deaths, is the most detailed analysis to date of a pattern first identified at least a couple of centuries ago, that more money translates into a longer life.

It could be as simple as this: Wealth buys higher-quality medical care, which allows people to live into old age. But a long line of evidence, including the new work, suggests it’s less obvious than it might seem. The affluent seem to live in healthier ways. They exercise more, smoke less, feel less stress and are less likely to be obese

There is a trove of information in the article worth discussing but the most intriguing line-of-thought involves understanding the cause and effect of geography and life expectancy. As the study states, higher-quality medical care is not the determining factor.

The new paper, in fact, finds little correlation between a region’s Medicare spending rate or the proportion of the population with health insurance and how long its poor citizens live.

One aspect the study and the NYT article did not consider is how access to information and knowledge through technologies such as smartphones and the Internet correlates with longevity.

I would like to propose a hypothesis: That longevity correlates with access to information. It is possible that in those cities and areas of the country where the poor live longer, they also have more access to modern technologies that allow them to inquire about matters of health-care and wellbeing.

It is worth noting that the study is the result of a collaboration between several academic, private and governmental organizations: the Department of Economics, Stanford University, Department of Economics, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, McKinsey and Company, Department of Economics, Harvard University, and the Office of Tax Analysis, US Treasury, Washington, DC.